-

More Light Than We Expected - online prayer service

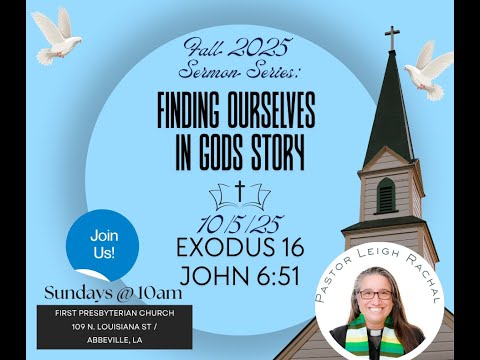

1.25.26 - Sermon written and preached by Leigh Rachal @ FPC Abbeville, LA

When I was little, one of the sweet things my folks would do when I was a baby was lift my arms up over my head and say, in a sing-song voice, “You are soooo big.”

Eventually, I learned my part in the ritual.

If someone asked, “How big are you?” I’d stretch my arms out as wide as I could and say, “Soooo big.”And as I grew, the phrase grew with me.

You rode your bike by yourself.

You said your lines just right.

You did that brave, hard thing.

You are soooo big.It was a way of naming growth.

Of celebrating becoming.

Of saying, look at the life unfolding right in front of us.So when I hear John 3:16, “God so loved the world,” part of me still hears that sing-song voice.

God loved us soooo much.

And that’s true.

God’s love is big. Vast. Uncontainable.And John is doing something even more specific here.

This verse isn’t actually telling us how much God loved the world.

It’s telling us HOW God loved the world.We might say, God thus loved the world.

This is the way God loved.Not from a distance.

Not in theory.

But by entering the world.

By taking on flesh.

By loving in a way that gives life, even when it costs something.God loved the world by coming into it.

And this world, John reminds us, is the same world that did not recognize him.

The same world that resists him.

The same world that would rather hide than be seen too clearly.Which is where Jesus goes next.

“This is the judgment,” he says.

Not that God condemns the world.

That is never God’s aim.

The judgment is that light has come.Light doesn’t wound, but it does reveal.

Light doesn’t shame, but it does uncover.

And sometimes what we uncover isn’t dramatic evil, but smaller things, fearful choices, narrowed lives, the quiet ways we try to protect ourselves by staying hidden.God loves the world.

And the world often loves hiding.Even the first story of sin is about trying to stay hidden.

Adam and Eve eat the forbidden fruit, discover they are naked, and immediately hide themselves from God.And so God loves the world by refusing to let it stay hidden.

Not to expose it for punishment,

but to bring it into healing.That is why Jesus talks about being born from above.

Not corrected.

Not scolded.

Not condemned or punished.

But re-born.

Re-created.That’s a theme in John.

Jesus is ushering in are-creation of the world.And so we must be

born from this new, revealing light.In the creed, we say Jesus is Light from Light. True God from True God.

If that is true, then as those who bear his image, we are created

by light. For light.

By love, for love,

meant to live as reflections of that true light,

which is self-giving love even now.Because darkness feels close these days.

Not abstract. Not distant.

Close enough to shape how we speak, how we see one another, how we move through the world.We see it in the headlines, war layered upon war, threats answered with more threats, human lives reduced to numbers or slogans.

We see it in a public life shaped by fear, where anger is rewarded and outrage travels faster than truth.

We see it in the exhaustion so many carry, the quiet sense that everything feels heavier, harder, more fragile than it used to.And if we’re honest, we don’t only see it out there.

Because darkness is not just something that happens in the world.

It is something the human heart learns to cling to.It shows up when fear convinces us we must protect ourselves at all costs.

When anger feels more honest than compassion.

When we begin to tell stories about others that make it easier not to love them.

When we stop believing that light can actually change anything.John does not let us pretend otherwise.

“This is the judgment,” Jesus says.

That light has come into the world,

and people loved the darkness.Not because they were beyond redemption.

But because darkness can feel safer.

Because hiding can feel easier than being seen.

Because light asks something of us.Light asks us to tell the truth.

Light asks us to see one another fully.

Light asks us to let go of the comfort of resentment and the illusion of control.God does not shine the light once and then withdraw.

God keeps shining.Again and again, God brings light into the world.

Not to trap us.

Not to expose us for punishment.

But because love refuses to give up on what it loves.God shines the light because God thus loved the world.

Loved it enough to enter it.

Loved it enough to give God’s very self.

Loved it enough not to let the world, or us, disappear into hiding.This is where belief comes in.

When John talks about believing in him or not believing in him, he is not talking about having the right answers.

Nicodemus already had answers.Belief here is about trust.

About where we place our hope.To believe in him is to live in the light.

To trust that God is light.

To trust that we are made in God’s image, meant to reflect that light into the world.It is to trust that God, not fear, is our salvation.

That love, not violence, is what ultimately saves.

That we are not meant to save ourselves.And when we stop trusting this,

when we dwell in darkness,

when we stop believing that our hope comes from God,

we begin to look elsewhere.We start to believe our hope lies in our own strength or cleverness.

We begin to think we alone can sort truth from lies.

We allow fear to turn neighbors into enemies.And John says something startling.

When we live this way, we are not waiting for condemnation.

We are already living inside it.Not because God has rejected us,

but because we have stepped away from the only thing that gives life.The path to salvation, John tells us,

is not power, or certainty, or self-protection.

It is love.

It is light.And here is the good news - grace.

God keeps shining that light.

Not to force belief,

but to invite trust.Again and again, God shows up.

God keeps loving.

God keeps refusing to let the world stay hidden.This is more than we expected.

We expect love to give up when itis resisted.

We expect light to retreat when it is rejected.

We expect judgment to look like punishment.Light keeps shining.

Love keeps giving itself away.To believe in him, then,

is to keep choosing to step into that light.

To trust that God’s self-giving love really is enough.More than enough.

More than we expected.The darkness is real.

And so is the light.And the light, John tells us,

has already come.Thanks be to God.

More Love Than We Expected

1.18.26 – Sermon written and preached by Pastor Leigh Rachal at FPC Abbeville, LA

John tells this story with intention.

It is early in his Gospel.

We had the great opening hymn telling us that Jesus is God and has been since before time began,

we were introduced briefly to John the Baptist,

Jesus performs his first sign of turning water into wine and then for his second act, he starts flipping tables…..

This story of Jesus standing up to the injustice happening within the temple comes much later in Matthew and Mark’s Gospel.

But let’s back up.

The Passover is near.

Jerusalem is crowded.

The Temple is full of sound and movement and bodies - all trying to do what faith requires of them.

Pilgrims have traveled long distances.

They have come to worship,

to offer sacrifice,

to draw near to God.

And into that sacred space, Jesus walks and does something no one expects.

He disrupts it.

Tables are overturned.

Coins scatter.

Animals are driven out.

This is NOT a gentle moment, and John does not try to make it one.

But neither is it chaos for chaos’ sake.

John presents this as a deliberate, embodied act,

a prophetic interruption meant to reveal something deeper than what can be seen on the surface.

Jesus is always more than we expected.

More generous than we imagined.

More challenging than we would prefer.

More disruptive of systems that no longer serve life.

To understand what Jesus is responding to, we need some context.

The Temple was the center of Jewish religious life,

and Passover was one of the great pilgrimage festivals.

People came from all over the region, often from far away.

Temple law required sacrifices to be made with animals that met certain standards,

and the Temple tax had to be paid in a specific currency.

That made money changers and animal sellers necessary.

In theory, they were there to help worship happen.

So the action of these money changers doesn’t begin as corruption.

It began as accommodation.

But over time, accommodation turned into exploitation.

As people realized that power and profit was possible…

Exchange rates became exploitative.

Prices went up beyond what the poor could afford.

Until the outer courts, especially the Court of the Gentiles,

became crowded with commerce,

leaving little room for prayer for those already on the margins.

Access to God was being sold.

Worship had become transactional.

Faith had become regulated.

Holiness had become managed.

In some ways, the money changers had already destroyed the Temple.

Not by tearing down stones,

but by hollowing out its purpose.

A building can remain standing long after its soul has been compromised.

The rituals continued.

The system functioned.

But what the Temple was meant to embody:

welcome, mercy, access to God,

was already slipping away.

Jesus steps into that space and refuses to let the exploitation stand.

John tells us that Jesus makes a whip of cords and drives all of them out of the Temple, with the sheep and the cattle.

The details matter here.

The whip is associated with moving animals, not beating people.

None of the Gospel writers describe Jesus as injuring anyone in this act.

There is no bloodshed here,

no call to arms,

no attempt to seize or hold power for himself.

But he does act in ways that are forceful and decisive.

He is confrontational.

And he stops a system in motion.

But it is not violence – not just because he does not harm bodies.

We can be violent in ways that don’t harm bodies.

But not only does Jesus not harm bodies.

He also does not dominate people or even seek to

He does not pass the risk downward to those unable to defend themselves.

Instead, he very decisively places himself in danger, instead of those who were being exploted.

Already, this is more than we expected, or at least very different from what we (and the people of the time) might have expected from a Savior….

This is not a Jesus who preserves the peace at all costs,

but a Jesus who refuses to let injustice hide behind the illusion of holiness.

This is not a Jesus who takes power for himself and his kingdom

but one who exposes the false-ness of a kingdom built on exploitative power.

When those in authority demand to know by what right he does this, they ask for a sign.

They want Proof. Authorization.

Something to justify such disruption.

Jesus gives them a strange answer. “Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up.”

I imagine they hear that statement as completely absurd.

Jibberish. Nonsense. Impossible bravado.

Maybe even as a threat….

But John tells us, the readers, his secret - the part his disciples cannot yet understand.

Jesus is speaking about his body.

This is the sign. The second sign of the Gospel.

Another way to see how God pours out God’s love for God’s people – refusing to allow people to be exploited or exploitative – knowing the harm that comes from both.

In John’s Gospel, Jesus’ signs are not about proving power or winning arguments.

Signs point beyond themselves.

They reveal who Jesus is and what God is doing,

often in ways that only make sense later.

Jesus is not saying, “Look what I can tear down.”

He is saying, “Watch what God will raise up.”

The disruption in the Temple is not the end of the story.

It is a sign pointing forward,

toward the cross and toward resurrection.

Toward a God who does not preserve life by force,

but brings abundant life through his own acts of self-giving love.

The danger comes when people read this story and imagine themselves as Jesus,

wielding a force of power against others “for God,”

rather than recognizing themselves as those whose own tables might need overturning.

Jesus’ disruption always moves toward mercy, toward access, toward life.

He overturns tables that are bringing economic harm.

He disrupts exploitation that are ruining the lives of both those being exploited and those doing the exploitation.

He clears space for prayer, not for domination.

And later, when violence does enters the story,

it does not come from Jesus.

It comes toward Jesus.

Everywhere in John’s Gospel, Jesus refuses violence,

even when it could serve his cause.

He rebukes the sword.

He stands unarmed before empire.

He absorbs harm rather than inflicting it.

We have to be careful when we read this and focus on the flipping tables.

Because we cannot take up the whip and leave out the wounded body.

We cannot take the disruption and discard the cross.

If an action moves toward fear, exploitation, domination, or harm to others,

John’s Gospel is clear:

That is not the way of Christ,

no matter how much scripture is quoted along the way.

This weekend, as we remember the life and witness of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., we see that Dr. King understood something Jesus embodied long before him.

The ends and means cannot be separated.

Violence cannot produce the peace God promises.

Force cannot build the beloved community.

Justice cannot be born from tools that deny human dignity.

Here is where this text presses us, gently but firmly.

If this moment in the Temple is a sign,

then it is not necessarily asking us to repeat Jesus’ actions.

It is asking us to recognize his way.

Jesus does not ask his disciples to follow him from synagogue to synagogue flipping tables.

He is not training them in outrage or spectacle.

He is showing them what God’s love poured out looks like in the real world:

It looks like disrupting injustice,

Even or perhaps especially when the acts of disruption come at great personal cost.

It looks like refusing to let God’s name be used to burden the vulnerable

or protect the powerful – or even ourselves.

It looks like absorbing risk rather than passing it on.

From this moment on, Jesus becomes the focus of attention.

The combined powers of religious authority and empire begin to close in on him.

The risk shifts toward him.

This sign places his own body in the path of what is coming.

And still, he does not turn away.

This is more than we expected…..

More courage than we anticipated.

More cost than we imagined.

More love than we thought possible.

To follow Jesus, then, is not just to reenact the disruption.

It is to embody the love it reveals.

It is to learn how to discern where injustice needs interrupting

and to ask who will bear the cost when that happens.

It is to choose presence over power,

mercy over fear,

trust over control.

If this sign teaches us anything, it is that God’s love does not avoid conflict,

but it does not preserve itself by force.

God’s love pours itself out for the sake of the world.

I think this is what the Psalmist meant by “Unless the Lord builds the house.”

When the Lord builds, what rises is not a fortress,

but a people shaped by mercy.

Not a system secured by fear,

but a community formed by courage.

Not a religion that must be defended,

but a life that can be given away.

This way of Christ may feel slower.

It may feel less impressive.

And it may feel far more costly.

But it is the way that leads to abundant life.

And that, is more than we could have ever dreamed or expected. Amen.

More Than We Expected

1.11.2026 - Sermon – written and preached by Leigh Rachal @ FPC Abbeville, LA

If John’s Gospel were a screenplay, it would begin with a wide lens camera angle.

Rather than easing us into Jesus’ life through family stories or familiar scenes,

John backs us all the way up before anything we would normally call history.

In the beginning was the Word.

Before light.

Before land.

Before life had taken shape.

John wants us to understand from the start that what he is describing is larger than the arrival of another religious teacher.

He is describing something that reaches into the fabric of creation itself.

That framing matters for how we hear today’s story.

At the wedding at Cana, we are witnessing Jesus’ first sign.

Throughout this Gospel, John doesn’t describe Jesus’s acts as miracles, but rather as signs.

Signs are meant to be read.

They point beyond themselves.

They reveal something true.

A sign shows you the direction you’re headed without taking you all the way there.

So this story isn’t simply about an impressive act.

It’s about what is being revealed.

John also tells us this happens on the third day.

That detail could easily be skipped,

but John doesn’t include it by accident.

In scripture, the third day repeatedly marks a turning point, or a miracle of sorts -

the moment when God acts in a way that opens up a future that had seemed closed.

On the third day of creation,

dry land appears and life becomes possible.

On the third day, Abraham reaches the mountain with Isaac

and discovers that death is not the final word.

On the third day, Jonah emerges from the depths

when survival had seemed impossible.

And, of course, on the third day, the tomb is found empty.

Again and again, the third day is the day when God’s action interrupts what human effort could not resolve on its own.

John has already taken us back before creation in the opening verses.

Now, with this first sign, he begins to show us that creation happening again. RE-Creation.

That helps explain why the setting matters so much.

This scene unfolds at a wedding.

A place of joy, relationship, and public celebration.

Nothing is broken at first.

No one is sick or desperate.

And yet something essential runs out.

The wine is gone.

In that culture, this would have been more than an inconvenience.

It would have marked the couple with lasting embarrassment.

Joy threatens to collapse quietly into shame.

Mary notices and brings the need to Jesus.

His response sounds abrupt to modern ears. “Woman, what concern is that to you and to me? My hour has not yet come.”

John isn’t portraying indifference here.

He’s marking a transition.

Jesus is stepping fully into his public ministry, and that ministry will no longer be governed by family expectation or social timing.

In John’s Gospel, Jesus’ “hour” always points toward the cross (not resurrection!).

It is the moment of the cross when Jesus’ identity is fully revealed.

Glory, in John, does not mean success or avoidance of suffering.

It means love given completely.

Jesus names that the hour has not yet come, and yet he still acts.

That tension tells us something important about God’s character.

God’s purposes unfold on a larger timeline, but human need is never ignored.

Jesus instructs the servants to fill the stone jars with water.

John tells us these jars were used for ritual purification.

They were part of the established religious life of the community,

meant to maintain order and readiness.

Jesus doesn’t discard them.

He uses what is already there and fills it fully. He full-fills their use.

And then the water becomes wine.

Not a small amount. Not barely enough.

There is an abundance, and the quality surprises even the steward.

This is not how things are supposed to work.

That surprise is part of the sign.

John is showing us that in this re-created world, God’s grace does not operate by the limits we expect.

Existing structures are not erased, but they are transformed.

What once served ritual obligation now serves shared joy as it was truly intended.

The steward never learns where the wine came from.

Grace often works that way.

Those who benefit from it aren’t always the ones who can explain it.

This brings us to today, the Baptism of the Lord Sunday.

Baptism, too, involves ordinary water carrying extraordinary meaning.

In our tradition, we are careful to say that the power of baptism rests in God’s promise, not in the water itself.

That promise does not depend on our memory, our age, or our understanding at the time.

Water itself helps make sense of this.

Scripture tells us that before anything else existed, God’s Spirit hovered over the waters of chaos.

Water moves. It cycles.

It changes form, but it doesn’t disappear.

The same water travels through clouds and rivers and oceans and bodies again and again.

When we speak of baptism, we are talking about being placed into an eternal movement of God’s faithfulness.

Whether we remember the moment or not, God remembers.

God remains faithful.

So when we renew our baptism today, we are not correcting something that was incomplete.

We are acknowledging a promise that continues to hold.

And from the water, we move to the table.

The wedding at Cana and communion belong together.

Both are signs of abundance.

Bread and cup come from the earth itself.

They rely on rain, soil, and time.

This table is not separate from creation.

It is creation sustained and shared.

This helps us see what John is doing across the Gospel.

John isn’t simply recounting the events of Jesus’ life.

He is describing a re-creation of the world.

In Genesis, creation begins with one man and one woman in a garden.

In John, the new creation begins with a wedding.

Community has widened.

Life has expanded beyond survival into shared joy and relationship.

And this story is pointing somewhere.

Throughout John’s Gospel, Jesus speaks of an hour that is coming.

When it arrives, it will take the shape of the cross.

That is where God’s glory is revealed.

Cana already gestures in that direction.

Wine is poured freely.

Joy is preserved.

In this story we see a generosity that refuses to let shame be the final word.

After this sign, John tells us, the disciples began to trust Jesus.

They didn’t suddenly understand everything.

They had simply seen enough to glimpse what kind of world Jesus was bringing into being.

That’s what signs do.

They don’t settle every question.

They invite trust.

Today, standing between font and table, we are invited into that same trust.

We are not simply remembering a story from long ago.

We are being situated inside it.

John’s Gospel doesn’t just invite us to admire signs from a distance.

It invites us to learn how to read them,

and to let them shape how we understand God, ourselves, and the world.

Over the months ahead, John will keep showing us signs.

Water that heals.

Bread that multiplies.

Sight given where there was only darkness.

Life spoken where death seems final.

None of these signs exist to impress.

Each one presses the same question:

What kind of world is God bringing into being through Jesus?

Cana answers that question in its own quiet but decisive way.

It tells us that God’s work of re-creation begins

not in isolation, but in community.

Not in scarcity, but in abundance.

Not by discarding what already exists, but by filling it until it becomes something more than it was before.

That matters for how we come to the font today.

We come not to prove our faith,

but to remember that God has already acted.

Long before we understood.

Long before we could name what we needed.

God’s promise has been moving toward us,

like water that never stops cycling through the world.

And it matters for how we come to the table.

We come trusting that what is offered here is not fragile or rationed.

We come believing that grace is not easily exhausted.

We come because this table belongs to the same God who saw a wedding on the brink of shame and quietly refused to let joy run out.

John begins his Jesus’ ministry here for a reason.

This first sign tells us what to expect from everything that follows.

It prepares us for a Messiah whose glory will not look like control,

but like love poured out.

A Messiah whose power is revealed not by avoiding suffering,

but by transforming it.

So as we move now to renew baptism and to gather at the table,

we do so as people learning how to read the signs.

Learning how to trust what they point toward.

Learning to believe that God is still at work, still creating, still expanding what is possible.

This sign does not close the story.

It opens it.

And we step into it together,

trusting that the God who once turned water into wine is still at work,

drawing creation toward a fullness we have not yet seen.

Thanks be to God. Amen.

Who We Are and Who We Are Not

12/28/25 – Sermon written and preached by Leigh Rachal @ FPC Abbeville, LA

They keep asking John the Baptist to explain himself.

Who are you?

What authority do you have?

Why are you doing this?These are not just friendly questions.

They are locating questions - A way of placing someone on the map.

Of deciding where they belong

and what weight their words should carry.

In Cajun culture, we have our own version of this question.

It sounds gentler, but it is asking the same thing:

“Who’s your momma?”

It is not just curiosity.

We aren’t just trying to figure out what your mother’s name is.

It is a way of understanding who shaped you,

where you come from,

what stories formed you.

If we know your people, we know something about you. We know how you belong.

When the religious leaders question John, they are asking their version of that.

Who are your people?

What line do you come from?

What role are you claiming in God’s story?

To understand John’s answer, we have to remember how this gospel begins.

John does not open with a birth story.

There is no manger or angel song.

John opens with poetry.

“In the beginning was the Word.”

Before anyone speaks in this gospel, before anything is explained,

we are told that Jesus is the Word that existed before creation itself.

The Word through whom everything came into being.

Then John immediately introduces another figure.

“There was a man sent from God, whose name was John.”

Not the Word.

Not the light.

But the witness.John’s gospel is careful here.

The Word comes first.

The light shines first.

John’s role is secondary, but essential.

He is the one who points.

The one who says, Look. Pay attention. Do not miss this.

So when the questions start coming in today’s passage, they make sense.

Are you the Messiah?

Are you Elijah?

Are you the prophet?In other words, are you the Word? Are you the light? Are you the one?

John answers by letting go. By clearing understanding who he is NOT.

“I am not the Messiah.”

“I am not Elijah.”

“I am not the prophet.”There is something deeply faithful about that acknowledgement.

John does not grab at power.

He does not inflate his importance.

He does not let himself be defined by what others want him to be.

Only after naming what he is NOT does he say who he IS:

“I am the voice of one crying out in the wilderness.”

Not the Word.

Just a voice.Not the light.

Just someone pointing toward it.In response to the questions asking John who he belongs to, he answers:

I belong to the work God is doing.

I belong to the truth.

I belong to the task of making room.

And then Jesus appears.

John sees him and everything sharpens into focus.

“Here is the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world.”

What does it mean for John to call Jesus the Lamb of God?

John does not explain the metaphor.

He assumes his hearers already feel its weight.

The lamb is a reference to Passover.

The lamb is about deliverance.

The lamb is a reminder of the blood on the doorposts and freedom on the other side the wilderness.

The lamb is how God moves people from bondage into life.Calling Jesus the Lamb of God is not about calling him meek and mild.

It is calling him the one who rescues his people.

And notice what John says next.

Jesus is the Lamb who takes away the sin of the world.

Not just individual guilt.

Not just private failure.

But the brokenness that runs through systems, relationships, bodies, and communities….

This is not about an individual transaction.

It is about communal liberation.

Which brings us back to light.

Earlier, John’s gospel tells us that the light shines in the darkness, and the darkness does not overcome it.

Light in this gospel reveals what is real.

It tells the truth.

That is why Psalm 32 belongs so beautifully with this story.

“Happy are those whose transgression is forgiven.”

“Happy are those in whose spirit there is no deceit.”This psalmist knows what hiding does to us.

The psalmist describes how silence dried them up.

How their body ached under the weight of what was unspoken.

But when the truth was named,

forgiveness did not arrive as some kind of punishment avoided.

It arrived as relief. As breath. As freedom.

That is what is happening at the river.

People are not lining up to be shamed.

They are coming to tell the truth.

They are stepping into the water because they are tired of carrying everything alone.

Tired of pretending.

Tired of being defined by what they cannot say out loud.

And then Jesus steps into that water.

Not to stand above them.

Not to separate himself.

But to join them.If we were asking the Cajun question of Jesus, “Who’s your momma?”,

the answer would not stop with Mary.

It would include the people around him.

The ones he stands with.

The ones he refuses to leave behind.

Jesus belongs with those telling the truth.

Jesus belongs with those longing for release.

Jesus belongs with those who have been carrying too much for too long.And he takes away sin not by ignoring it,

but by removing its power to define us.

By carrying it out of hiding.

By refusing to let shame have the final word.

We live in a world that keeps asking us to explain ourselves.

To justify our worth.

To prove our belonging.

Even faith can become another performance, another way of hiding.

John offers another way:

Let go of what you are not.

Tell the truth about who you are.

And point to the One who has already come close.Psalm 32 promises what waits on the other side of that honesty:

Happiness, not the shallow kind, but the deep relief of being known.

Freedom that settles into the body.

Joy that comes from discovering you were never alone.

John’s witness is simple:

This is the Word made flesh.

This is the light that tells the truth without destroying us.

This is the Lamb who takes away what no longer needs to be carried.And we are invited into that same vocation.

Not to be the Word.

Not to be the light.

But to be witnesses.Witnesses to grace that frees.

Witnesses to truth that heals.

Witnesses to a God who enters the water with us and calls us beloved.May God grant us the faith and the courage to be a worthy witness to his Amazing Grace. Amen.

Waiting with God

12/21/25 – Sermon written and preached by Pastor Leigh Rachal @ FPC Abbeville, LAWaiting with God

My dad used to drive a mile or more out of his way just to avoid stopping at a red light.

It did not matter if the alternate route took longer.

It did not matter if it burned more gas.

What mattered was not having to stop and wait.

I think that, for him, waiting felt like wasted time.

Or maybe like being stuck.

I definitely got my own discomfort with waiting from him.

As you all might remember, for the past two Epiphanies, my star word has been pause.

And for the past two years, I have proceeded to do very little pausing at all.

Life just keeps barreling forward at lightning speed.

Calendars fill up. One thing leads to another.

I will look up and realize the day is gone…

I do not pause well.

I do not wait well.

Perhaps this is part of why I insist on observing Advent

- because I know that we could all use a bit of help learning to live in the waiting.

Advent means waiting.

That’s what Advent is about.

Waiting to celebrate the birth of Christ.

But also waiting for Christs return

and the day when all that was started by Gods indwelling will finally be made right.

Advent is a time for preparing but also for pausing.

It is a time for waiting

but it is not inaction.

We are not at some holy red light just tapping our foot until Jesus gives us the green light again.

Advents active waiting is a bit like pregnancy….

As a child is stitched together in the womb,

the work of preparing the outer world for the child’s arrival is also going on.

And that task list can feel endless:

Paint the nursery.

Assemble the crib.

Stock up on diapers.

But there is also a good deal of inner work that must also happen during those months of pregnancy…..

turning regular women and men into moms and dads.

It is an identity shift of huge magnitude.

A friend of mine once commented, as their due date flew past,

that it was a very good thing that his wife’s pregnancy was going a bit longer,

because he wasn’t sure he was quite ready….

Of course, in other moments, waiting can feel like eternity….

And we wonder why it isn’t happening already.

There is a meme that circulates about pregnancy that feels painfully accurate.

It says most months have 30 days. Some have 31.

But the last month of every pregnancy has approximately 125,789 days.

Funny how that works out.

Sometimes time does seem to stretch when we are waiting for something that matters.

This can happen in moments of joyful anticipation as well as those moments of agonizing unknowing or fear or worry.

Minutes slow to a crawl.

Days feel endless.

Waiting has a way of bending time itself.

Psalm 130 knows this kind of waiting.

“I wait for the Lord, my whole being waits.”

This is not polite waiting.

Not calm, well-behaved waiting.

This is whole-being waiting.

The kind of waiting that changes who you are.

The kind of waiting that settles into your body.

The kind that tightens your chest.

That makes it hard to breathe.

The kind of waiting that knows what it is to live in the depths.

And still, the psalmist says, “In God’s word I hope.”

Advent does not rush past that tension.

Advent does not pretend waiting is easy or holy just because we slap a candle on it.

Advent lets waiting be what it is: hard and honest and unresolved.

Then John opens his Gospel by pulling the curtain all the way back.

“In the beginning was the Word.”

Before clocks.

Before calendars.

Before deadlines and red lights and long months that refuse to end.

The Word was already there.

John tells us that everything came into being through this Word.

That light shines in the darkness, and the darkness does not overcome it.

John doesn’t denial the darkness.

John is clear that the Darkness is real, but it is NOT ultimate.

This beautiful hymn from John uses the language of Eternity.

We are talking about Cosmic things, it seems.

And sometimes that can feel a bit distant... A little abstract.

Until John says the sentence that changes everything:

“The Word became flesh and lived among us.”

In that moment - before all time,

The eternal stepped into the ordinary.

The timeless entered time.

Metaphysically speaking, time only exists in this world.

God, of course, does not need clocks or schedules or countdowns.

And yet, the Word chooses to enter this realm.

Chooses to inhabit time with us.

God agrees to days and nights.

To seasons

And delays.

To growth that cannot be rushed.

The incarnation is not just God taking on flesh.

It is God agreeing to live inside human time.

God has come…. To wait. With US.

God does not detour around the red lights of human life.

God stops at them.

God grows slowly in the pregnant pauses.

God waits for the right moment.

God waits through silence.

God waits through grief.

God waits through that long in-between where nothing seems to be happening, and yet everything is….

We wait for resurrection – which does not even happen the moment Jesus dies.

Love waits through Holy Saturday.

Hope takes its time.

In my impatience, especially at Advent, I can find myself asking:

So what is God waiting for?

I know it isn’t:

Perfection. God has never asked that of us.

It is not efficiency….

And God is not waiting for the world to finally get it right.

I think God waits for ripeness.

Like a farmer waiting for the right time to harvest…

God waits…

For hearts that will be able to recognize resurrection life when it rises around them.

For healing that will not shatter fragile souls.

For love that can be received instead of resisted.

Bethlehem tells that story quietly.

As the God-child is born….

In a small town. An ordinary place.

There is no shortcut.

There is no spectacle.

Just a long night where God arrives without hurrying the moment.

Waiting does not mean nothing is happening.

Waiting is often where the deepest work is unfolding,

beneath the surface,

out of sight.

John tells us the light shines in the darkness.

Not once the darkness is gone.

Not after the waiting is over.

The light shines now.

Psalm 130 promises that with the Lord there is steadfast love,

and with God there is great power to redeem.

But redemption is not rushed.

It unfolds.

It grows slowly.

It takes time.

This is the good news:

We do not wait alone.

We do not wait for a God who is distant or delayed.

No - We wait with a God who has entered time itself.

A God who inhabits our waiting.

A God who agrees to be here,

full of grace and truth,

even when time stretches and hope feels thin.

So when waiting feels endless,

when days crawl,

when we find ourself tapping our foot at the red light, we can remember…

God is not outside of time, urging us to hurry up.

God is inside it.

Waiting with us

And that makes even the longest pause holy ground.

Thanks be to God. Amen.

The Grace We Are Seeking

12.14.25 – Sermon written and preached by Leigh Rachal @ FPC Abbeville, LA

Introduction to Isaiah 55:1–13

Last week, we heard Ezekiel speak to a people in exile, standing in the ruins of what once was, and daring to imagine life where there had been only loss.

Today, Isaiah addresses that same displaced community, still living far from home, still unsure whether return and restoration are truly possible.

It is important to realize that these words are spoken - not after everything has been resolved, but while the people are still in exile, still scattered and in many ways, shattered.

Listen now for the word of God as it comes to us through the prophet Isaiah.

Introduction to John 4:13–14

As we read these stories through the lens of the Gospel of John, we encounter a Samaria woman at a well, an ordinary location that becomes the setting for an unexpected conversation.

This brief portion comes from the middle of that encounter, grounded in the daily rhythms of life and shaped by long-standing boundaries that frame the scene.

Listen now for the word of God as it comes to us through the Gospel according to John.

Sermon: The Grace We Are Seeking

Isaiah’s words sound lyrical because they are.

This section of Isaiah is part of a larger song or poem.

I have been wondering if perhaps we could call it a psalm of Isaiah.

It opens and closes with proclamations of redemption.

With release.

With the promise that something has been paid, something has been set right.

This song of redemption, points not to a vague spiritual idea, but to something more concrete.

Redemption is the paying of a debt.

To be redeemed is to have what binds you released.

To have access restored.

To be freed from what kept life out of reach.

But this song is sung not in a moment of triumph,but to a people in exile.

Isaiah is addressing people whose city has been destroyed, whose temple is gone, whose lives have been upended.

They are far from home, living under systems they did not choose, learning how to survive in a world shaped by scarcity and loss.

And into that reality, Isaiah does not offer modest hope.

He does not say “One Day, Every Little Thing Is Gonna Be Ok”

Isaiah sings about abundance right now.

“Come, all you who are thirsty.”

“Come to the waters.”

“Come without money and without price.”

He is using redemption language.

Debt language.

Presbyterians are one of the few traditions who have prayed the Lord’s Prayer asking for debts to be forgiven, not just sins or trespasses.That choice reminds us that redemption has economic undertones,

even when it is not about the U.S. dollar, or any nation’s currency.Of course, sometimes, it is about actual money too!

But we pray collectively for the forgiveness of debts because we know that brokenness and sin are not only personal.

They are structural.As we ask for our own debts to be forgiven,

We also ask for forgiveness for the ways we exploit others,

for the systems we benefit from,

for the ways we participate in scarcity rather than abundance.And we remember that these things are connected.

Forgive us our debts, as we forgiven those who are indebted to us!

Isaiah’s song imagines a people no longer defined by what they owe, what they lack, or what they cannot access.It imagines a world reordered by grace and abundance.

Isaiahs song reminded the original hearers. And us.

That even in the midst of scarcity.

Even in the midst of crushing debts for some and huge profits for others.

Even in the midst of chaos and devastation,

God has not stopped imagining a world ordered by grace and abundance.

There is a game my kids like to play sometimes.

As I move through the house, folding laundry or starting dinner or heading toward the next task, they quietly sneak up behind me.

They fall in step just a pace or two back.

They follow me from room to room without saying a word.

So I keep going, assuming I’m on my own.

And then I turn around suddenly and there they are, right behind me.

Close enough to startle me.

Close enough that it’s clear they’ve been there for a while.

Sometimes my experience of God is like that.

I’m going about my day, managing responsibilities, dealing with what’s in front of me, trying to meet the basic demands of life.

Maybe I remember to pray.

Maybe I don’t.

Maybe I’m seeking God.

Maybe I’m just trying to get through the day.

And then I realize God is here.

Now.

Already.

Isaiah’s song, and the gospel story we heard today, both tell us that God does not wait for ideal conditions.

God does not wait for us to be spiritually focused or even actively searching for God.

God shows up in exile.God shows up among people who are scattered and shattered.

God shows up in ordinary days.

God shows up right behind us, beside us, even when we assume we are on our own.

Which brings us to a Samaritan woman at a well - not looking for God, but just looking for water.

She is seeking access to something basic.

Ordinary.

Necessary.

She is meeting the demands of daily life.

And Jesus is already there.

Even for the Samaritan woman.Samaritans, of course, were not friends of the Jews.

Samaria was the capital of the northern kingdom of Israel. But when the Assyrians conquered that land, the Jews living there began to intermingle with the Assyrians and so the Jews of the southern kingdom (Judah) began to see them as a watered down, corrupted version of the true kingdom...

The division was about race, and culture, and politics, and religion, and economics… because of course it was.

John’s Gospel is pointing out that Jesus is not just for who we think is the in-group and God’s plan for redemption of the world is not just for some in-group in our day either.

God shows up even for those we might think undeserving.

Even for those not looking for more.

Even for those whose hopes have narrowed to just survival.

Jesus does not shame this woman’s ordinary hunger. Bodies still need water.

Lives still require food, shelter, care.

God is not offended by basic need.

But Jesus offers more than she could reasonably think to ask for.

“Everyone who drinks of this water will be thirsty again,” he says, “but those who drink the water that I will give will never thirst.”

The promises of God stretch beyond our own rationality.

Isaiah’s song sounds a lot like the concept of Jubilee to me.

Jubilee years in the Hebrew Scriptures were supposed to be held every 49 years. They were a time when

Debts would be released.

Access would be widened.

Abundance would be shared.

Jubilee was about joy breaking out where there had been only endurance.

The jubilee, Isaiah, Jesus…

All are reminding us of Gods dream for this world. A dream of abundance and grace.

Everyone who thirsts should come and drink.

There is no price that we have to pay.

God has purchased it for us.

There is enough for all.

And much like it did for Isaiah’s world, this dream of God’s still feels like an irrational impossibility.

We live in a world where access to food, clean drinking water, healthcare, housing, and basic human dignity is contested every single day.

We live in a time when we are told that scarcity is inevitable and abundance unrealistic.

Into that world, God keeps singing a different song.

Which is why the invitation this Sunday is not simply to find God or seek God, as though God were missing.

God is already here.

At the well.

With people who are scattered or shattered.

Walking quietly behind us through our ordinary days.

Our invitation is to seek God’s dream.

A dream where debts are forgiven and access is shared.

A dream where communities are shaped by abundance rather than fear.

A dream where joy is not a private possession but a collective reality.

We are called together to build a world, a community, a way of being, a people shaped by that vision.

God has already set the vision before us.

Not as a fantasy.

Not as wishful thinking.

But as a reality that already breaking in to our world.

Joy flickers today not because the work is finished, but because the world God dreams of is already here among us.

We are invited to believe it is possible.

And then to live our way into it.

May we do so with faith and courage. Amen.

Breath Enough for the Valley

12/7/25 – Sermon Written and Preached by Leigh Rachal @ FPC Abbeville, LA

INTRODUCTION TO EZEKIEL 37:1–14

Last week, we heard Isaiah speak hope to a people frightened by the collapse of all they knew.

Today we step deeper into that history.Jerusalem has fallen,

the people have been carried into exile,

and hope feels shattered.

Into this landscape of loss, God gives a vision to Ezekiel that insists the story is not over.

Let us listen for the Word that breathes life where life seems impossible.INTRODUCTION TO THE GOSPEL — JOHN 11:25–26

We continue hearing the stories of the Hebrew Scriptures through the lens of John’s Gospel.

As God promised life to bones that were long dead,

Jesus now stands beside Martha at her brother’s tomb and speaks a promise stronger than grief. He says:

“I AM the resurrection and the life.”

Let us listen for how Christ’s abundant life meets us even in the places we fear are beyond hope.

ADVENT 2 SERMON — PREPARE

“Breath Enough for the Valley”

Ezekiel 37:1–14; John 11:25–26

When Harper was about four years old, he was staying with my mom and my stepdad, Ralph during an ice storm.

He and Ralph had bundled up, walked outside into the sleet, and built a small icy snowman.

It was the kind of wobbly creation that only a Louisiana child and a grandparent would have the patience, much less the desire to make.

But it came out pretty cute.

At some point, Ralph went back inside to get a hat for the snowman.

As he rounded a corner just out of sight, his feet slipped out from under him on the icy path.

He fell hard and sliced his head open.

He lost consciousness for a few seconds, then came to and stumbled inside.My mom sat him down, trying to clean him up, trying to piece together what had happened, and realizing he didn’t quite know himself.

So she called me to come get Harper so they could head to the ER.

By the time I arrived, they were wiping away the last of the blood and getting ready to go.

I stepped through the door ready to just scoop Harper up and head out quickly so that he wouldn’t be too traumatized by it all and so they could be on their way to get Ralph help.

But before I could reach him, Harper’s scared little face lit up.

He ran—not to me, but to his Ralphie—and wrapped his arms around him.

And with all the confidence a four-year-old heart can hold, he said,

“It’s ok, Ralphie. It’s gonna be ok. Momma’s here now.”

In his little mind, my presence could still heal anything.

Momma could fix anything.

My presence made his own fear lose its sharp edges.

And he was sure I could offer that to his Ralphie.

He didn’t understand what had happened and he knew that he couldn’t make it right on his own...

But he knew someone he trusted to make the world less scary and less painful.

And in that turning, in that instinctive leaning toward presence,

he prepared a small but holy space for hope in his own heart.

I think these moments are what Scripture is referring to when it tells us that “a little child will lead us” or when it invites us to have the faith of a child….

And Advent invites us into that kind of faith and that kind of preparation:

Not the hurried preparation the world expects.

Not the endless lists or the pressure to perfect.Advent preparation is quieter.

Gentler.

It is the clearing of a little room inside ourselves so breath can return.

We prepare by turning toward God with open hands and honest hearts.

Advent is when we lean into trust and say to God, “This mess is too big for me, but your presence can hold it and heal it.”Ezekiel lived through the devastation of the Babylonian exile.

Jerusalem had fallen.

The temple lay in ruins.

Families had been carried off to Babylon.

Everything that once felt steady was gone.The people repeated the same sentence to each other, like a psalm of despair: “Our bones are dried up. Our hope is lost. We are cut off.”

And Ezekiel felt it too.

He had been a priest-in-training for a temple that no longer existed.

His own calling had crumbled with the stones of Jerusalem.So when God places Ezekiel in a valley of dry bones,

God is not showing him someone else’s catastrophe.

God is showing him the truth of where he is standing.

The valley is a mirror for him and his people.Can these bones live?

It is a question that echoes through every age, every grief, every valley we walk.

Ezekiel cannot imagine how life could return,

but he makes one small opening for hope:

“O Lord God, you know.”

This is not certainty.

This is not a solution.

He has no idea how it might be possible,

but he makes just enough room to think that

maybe God could make these dry bones live again.

And into tiny window of hope, into that prepared room, God breathes.

Breath rattles the bones.

Breath knits sinews and flesh together.

Breath fills lungs that had long forgotten how to breathe.

Life stands again on feet that had grown used to the dust.This is God’s way…

Life begins with breath.

Hope begins with breath.

Resurrection begins with breath.We see it again John’s Gospel - in Bethany.

There is a house full of mourners,

a sister grieving her brother, and a tomb sealed against the world.This is another valley.

Another moment when breath feels absent.And Jesus stands right there, close enough to touch the grief in Martha.

Close enough to hear the tremble in her voice.

Close enough to feel the weight of death in the air around them.And before anything changes,

before the stone rolls away,

before Lazarus steps into the light,

Jesus says,

“I am the resurrection and the life.”This is not a promise about a distant someday.

It is a declaration of presence in that moment.

Life is here.

Hope is here.

Breath is here.

Christ is here.And Martha, much like Ezekiel, makes a small but holy room for trust.

She cannot imagine how resurrection could come.

She cannot yet see what Jesus sees.

But she turns toward him and in doing so, she prepares just enough space for life to rise.Advent is the season that teaches us to prepare that kind of space.

Not perfect space.

Not polished space.

Just honest space where God can breathe.Sometimes preparation is a candle lit in a dark room.

Sometimes it is a whispered prayer.

Sometimes it is the steadying breath taken before facing another day.

Sometimes it is leaning toward someone we know who can hold what we cannot.

Sometimes it is the smallest turning toward God, a childlike trust that says, “It’s ok. I know you are here now.”And so, as Advent walks us toward the Babe Born in Bethlehem,

let us return to this breath:

Breath that sweeps across the valley of bones.

Breath that warms the body of Lazarus.

Breath that fills the lungs of a newborn child.

Breath that echoes through prophets and angels and shepherds and seekers.

Breath that still moves, still stirs, still brings life to the places we fear are too far gone.Advent and Christmas teach us that resurrection does not always begin with trumpets and fanfare.

Sometimes it begins as a breath so faint we almost miss it.

Sometimes it begins as a quiet stirring in a valley that has been dry for a long time.

Sometimes it begins with a child’s instinctive turn toward the presence that makes them feel safe.This season invites us to trust that breath again.

To notice the movement of God gathering what has been scattered.

To feel life rising inside places we had given up on.

To recognize Christ beside us, speaking resurrection into our sorrow.Today, as the Advent candles flicker their soft, determined light,

may we notice the breath of God moving in us, around us, and through us.

May we feel life stirring in places that once felt silent.

May we trust the Spirit who still knits bone to bone and calls us to stand.Even the Christmas hymn reminds us that

before we can shout “Joy to the World”,

“every heart” must “prepare him room”.

Before heaven and nature sing,

we must invite the God who meets us with resurrection breath

to fill our lungs with courage

and make us ready for abundant life.

Amen.

Trust: God's presence meets us in the fire

11.30.25 - Sermon written and preached by Leigh Rachal @ FPC Abbeville, LA

SCRIPTURE INTRODUCTION (Daniel 3)

Last week, we listened as the prophet Jeremiah spoke to a people living in uncertainty, urging them to build and plant and seek the peace of the place where they found themselves exiled.

Today we remain in that same long season of displacement, but we turn to another voice from the exile, another glimpse into what faith looked like for a people trying to remember who, and whose, they were.

By the time we meet Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego, the Babylonian empire has not only conquered their land but tried to reshape their identity, language, and loyalty. Everything familiar has been stripped away. Everything stable has been shaken.

And yet, in the midst of that dislocation, today’s reading shows us what steadfast faith looks like when the world around you is demanding compromise.

Let us listen for a word of hope, a word of courage, and above all, a word of presence.

GOSPEL INTRODUCTION (John 18:36-37)

We continue hearing these ancient stories through the lens of John’s Gospel, which keeps pulling us back to the God who draws near, who abides, who chooses presence over power.

Let us listen for that same nearness in today’s Gospel reading.Advent 2025: Preparing Our Hearts for the God Who Draws Near

Sermon for Advent Week One: Trust – God’s presence meets us in the fire.

Have you ever stepped into a pitch-black room

and felt that momentary wash of disorientation

where everything in you tightens because you cannot see

what is in front of you?You stand still….. waiting….

your heart beating a little faster than usual……And slowly, slowly… your eyes begin to adjust…..

And you realize the room is not entirely dark after all….There is a sliver of light coming from somewhere,

maybe a thin line under the door,

or a soft glow from a window you had not noticed,

or perhaps there is a faint reflection your eyes needed time to recognize.And that tiny bit of light,

as fragile as it seems,

is enough…..Not enough to see everything.

Not enough to feel certain or safe or in control.

But enough to take the next step.

Enough to know you are not lost.

Enough to remember that darkness is rarely absolute and never final.Advent begins a bit like that.

Not with full illumination.

Not with answers.

But with the slow realization that there is light already present in the shadows

if we are willing to pause long enough

for our eyes to adjust.Advent always starts in the places where shadows linger.

The shadows of exhaustion.

The shadows of grief that sits heavy on the chest.

The shadows of a world stretched thin by worry and weariness.

The shadows where we ache for God to come near.And into those shadows come the old stories that have carried God’s people for generations.

Stories that remind us of who God has been.

Stories that tell us what God is still doing.One of those stories begins with three young men whose names feel like courage themselves:

Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego.

But those were not the names their mothers gave them.In chapter one of the book of Daniel we learn their true names, their Hebrew names:

Hananiah, which means “The Lord is gracious.”

Mishael, which means “Who is like God.”

Azariah, which means “The Lord has helped.”

These are names that carried the memory of the Holy One.

Names rooted in their identity as the people of God.But Babylon tried to rename them.

Tried to reshape them.

Tried to absorb them into a system where allegiance to the king

mattered more than faithfulness to God.The world still does this.

It still tries to rename us.

We are often renamed by our failures,

our exhaustion,

our fear,

our scarcity,

our status,

our usefulness.The world often tries identify us (or cause us to identify ourselves) by the wounds we carry….

But those are not our true names.

Just as Hananiah remained Hananiah

even when the empire called him Shadrach,

we remain who God has always said we are:

We are Beloved.

We are the Children of the Most High.We are chosen. Forgiven, and set free.

No empire, no system, no season of hardship

can rename someone God has already called beloved.Hananiah, Mishael, and Azariah were taken from their homeland,

educated in the king’s court,

surrounded by a culture that rewarded conformity and punished any sign of resistance.

Everything around them whispered that survival required surrender.

But they remembered who they were and to whom they belonged.So when the king demanded allegiance,

when music played and the crowd knelt low,

they stood tall.

Not out of pride.

Not for attention.

But because their faithfulness ran deeper

than their fear of the consequences.Their courage carried a cost.

And that cost was fire.And God showed up.

Not later.

Not once the flames died down.

Not from a safe distance.

But right there in the blaze itself.It does not surprise me that God met them there.

This is who God has always been.Through the deep waters, God says, I am with you.

In the valley of shadows, you will fear no evil, for I am beside you.

When the flood rises, it will not sweep you away.

Not because we are strong enough to stand on our own,

but because God is steadfast enough to stay…..In every story of God,

Before deliverance, there is presence.

Before rescue, there is companionship.

Before the ending we long for,

there is the God who steps into the fire and makes it holy ground.And if that is who God has been,

then that is who God still is.Which means when we quietly think the question that we rarely dare to ask out loud:

Can you meet me too, God?

we ask the One who has already walked through flame for us….And still, I find myself asking:

God, can you really meet us in the dumpster fires of today?

Can you meet the single mom in line at the grocery store,

standing under flickering fluorescent lights,

and calculating every dollar…

sliding items out of her cart one by one,

because the rent is due

and her paycheck is small

and the fire of “not enough” keeps creeping closer?Can you meet the weary ones

at the graveside of someone beloved,

with their hearts burning in grief that seems like it will never ease up,

because their world has shifted beneath their feet?Can you meet families walking through season after season

of uncertainty and worry,

carrying hope in one hand

and heartbreak in the other,

all while doing their best to hold onto each other together

in a world where stability is fragile?We may all feel different flames.

But there is the same pressure:

The pressure to bow.

The pressure to harden.

The pressure to shrink our compassion so our hearts do not break quite so easily.

The pressure to match the world’s fear.

The pressure to settle for cynicism

or lose ourselves in distraction

or forget who and whose we are.And yet.

God keeps stepping into fires.

God keeps breathing life into bones that feel dry and exhausted.

God keeps parting waters that looked ready to drown us.

God keeps carving pathways through the wilderness.

God keeps bringing green shoots out of barren seasons, and blooms in the desert soil.This is who God has always been:

Strength when we are weak.

Breath when we are empty.

A presence in the fire.

A companion in the valley.

The light that does not wait for morning.Advent does not ask for certainty.

But Advent asks for trust.Trust that God has and will – and even now does draw near

to the places we thought were godforsaken.Trust that God comes to the rubble, and can turn it into places of beauty.

Trust that God is already standing in the fire we are naming for the first time.

Trust that the fourth figure still walks among the embers of our life,

still turns the empires punishing furnace floors into holy ground,

and still draws close enough to whisper through the smoke,“I am here.

Even in this.

Especially in this.”So we begin this Advent season watching for God who has always shown up in the shadows of death,

in the quiet corners of grief,

in the places too small or too broken to seem holy.We begin this season trusting not in our own ability to hold it all together,

but rather, trusting in the One who keeps finding us right when and where the world says we should not expect to be found.As God who draws near and stands with us.

We see that it is God who lights the first candle in the very heart of the darkness.

Thanks be to God. Amen.

The Light We Call By Name

11.16.25 – Sermon written and preached by Leigh Rachal @ FPC Abbeville, LA

Scripture Introduction: Isaiah 9:1–7

The world Isaiah speaks into is a world in crisis.

By the time of this passage,

the Assyrian Empire has swept through the northern kingdom of Israel.

Entire regions have been conquered.

Towns and villages have been emptied.

Families have been uprooted.

The places Isaiah names were the first to fall and their loss hangs over the whole nation like a heavy shadow.

Isaiah himself lives in Judah, the southern kingdom,

watching the devastation to the north

and knowing his own people feel the danger pressing closer.

The fear is real. The uncertainty is real.

Life has shifted in ways no one expected, and the darkness feels deep.

It is into that landscape that Isaiah steps forward as a prophet.

Not to erase the fear, not to deny the reality,

but to speak a word from God in the midst of it.

Let us listen for the Word of the Lord in the book of Isaiah.

Isaiah 9:1-7

Scripture Introduction:

Our second reading comes from the Gospel of John,

in the midst of one of Israel’s great festivals, the festival of booths or tabernacles.

It is a time when the people remembered how God guided them through wilderness nights as a pillar of cloud and fire.

Lamps were lit across the temple courts.

Their glow filled the courtyards and reminded the people of God’s presence with their ancestors long ago.

It is in that setting, surrounded by their collective memory of God’s guiding light in the wilderness, that Jesus speaks.

Let us listen for the Word of the Lord from the Gospel of John.

John 8:12

Again, Jesus spoke to them, saying, “I am the light of the world. Whoever follows me will never walk in darkness but will have the light of life.”

Sermon: The Light We Call By Name

I sleep with my phone nearby.

Not for the notifications.

Not even for the alarm.

Mostly for the light…..In the middle of the night, when the house is quiet and the room is dark,

all I have to do is tap the screen.

The glow is not much.

It will never brighten the whole room or chase away every shadow. But it is enough.

Enough to see the floor.

Enough to keep from stepping on the dog’s tail.

Enough to make my way without stumbling.It’s just a tiny bit of light.

But in the middle of the night, it changes everything.Isaiah spoke into a moment that felt like that kind of night.

A moment when the world had dimmed around God’s people.

A moment when they were trying to find their footing in a landscape that had shifted under them.

The northern tribes, Zebulun and Naphtali,

had already fallen to the Assyrian empire.

These were not distant places.

These were neighbors. Kinfolk.

These were the lands where cousins lived,

the lands whose stories filled the collective memory of the people.

Now they were occupied.

Their people displaced.

Their identity shaken.

Assyria was not only a political force.

It was a shadow that spread across everything.

One couldn’t do anything without fear…

Every border crossing. Every trip to the marketplace. Was done in fear.

Every prayer. Every plan for tomorrow. Was done in the shadow of that fear.

The fear was not imagined.

It had a shape and a name and an army.

And it was close enough to breathe down their necks.This scripture passage calls what they are living in “deep darkness.”

Interestingly, the same old Hebrew word used here is found in Psalm 23, which we usually translate as “the shadow of death.”

This darkness was not merely nighttime.

This was the kind of darkness that settles into a community

and rearranges how people live and think and hope.

Isaiah steps into that world.

Not with easy reassurance.

Not with denial.He steps into the same shadows everyone else is standing in.

He breathes the same air.

He carries the same questions.

And yet he speaks.“The people who walked in darkness have seen a great light.”

When Isaiah says that, nothing has changed…. yet.

Assyria is still Assyria.

The land is still scarred.

The people are still afraid.

Hope has not arrived.

Peace has not broken through.But Isaiah sees what the people cannot see yet.

That God’s presence has not left.

That the darkness is not the end of the story.

That light has a way of coming even when no one is looking for it.Isaiah even names the direction the light will come from.

He points north.

Toward Galilee.

Toward the very regions crushed first by Assyria.Isaiah says the first light will rise

in the very places that have known the worst of the night.

Because this is the pattern of God.

God’s light does not begin where everything is already bright.

God’s light begins where people most need it.Isaiah then imagines what this light will do.

It will break the yoke from their shoulders.

It will lift the weight that has pressed them down.

It will burn the tools of violence that have scarred the land.

It will end the cycle of fear that has shaped their days.This is not sentimental light.

It is liberating light.

Restoring light.

Healing light.

Light that does not pretend the world is fine.

Light that enters what is not fine and begins its quiet work of restoration.Isaiah then tells them that this light will take form in a child.

A child born into a world that is not gentle or safe.

A child who will carry titles large enough to signal that God’s reign is coming in a new way.Wonderful Counselor.

Mighty God.

Everlasting Father.

Prince of Peace.This is clearly a new kind of leadership.

Not based on fear.

Not rooted in domination.

Not held together by violence.

A leadership rooted in God’s own character.

A leadership that creates peace by healing and justice, not by force.Centuries later, during the Festival of Booths, Jesus stands in the temple courts.

This is a festival built entirely around the memory of wandering in the wilderness,

the memory of God’s guidance,

the memory of a pillar of fire that lit the way through every night.

During this feast, giant lamps were lit in the courtyard.

Their glow could be seen across the entire city.

The light reminded the people that God had guided them before and could guide them again.

It is in the glow of those lamps that Jesus says, “I AM the light of the world.”

Not the festival lamps.

Not the temple lights.

Jesus himself.Jesus stands there as a human being.

Carrying in his own body the fulfillment of Isaiah’s promise.The same light that rises in deep darkness.

The same light that breaks the weight of oppression.

The same light that guides people through wilderness nights.

The same light that whispers, even now, that the shadow of death will not ultimately win.Jesus becomes the light that is enough.

Enough to reveal truth.

Enough to heal wounds.

Enough to enter the parts of our lives we keep hidden because we worry they are too dark or too tangled.

Enough to quiet the frantic stories we tell ourselves in the night.

Enough to steady us when the world shifts under our feet.In church, we talk a lot about peace.

Sometimes the images of peace feel soft and beautiful.

But sometimes, if we are honest, they feel too small for the world we actually live in.

Sometimes we find ourselves longing for something deeper than holiday peace,something that can stand up to grief and violence and exhaustion and uncertainty.

Isaiah and Jesus offer that deeper peace.

A peace that does not ignore reality.

A peace that looks directly at the world as it is.

A peace that enters the real valleys, the real upheavals, the real shadows.

A peace that holds even when nothing else does.And so the promise for us today is this:

God’s light will rise.

God’s presence will meet us in every shadowed place.

God’s peace will take root in the real world.Sometimes the light comes like morning.

Sometimes it comes like a lamp in the distance.

Sometimes it comes like the soft glow of a phone screen in the night.

It is not always bright.

But it is always enough.

Enough to take the next step.

Enough to know we are not alone.

Enough to trust that the One who is our light will guide us all the way home.Thanks be to God. Amen.

Come to the Water

11.9.25 – Sermon written and preached by Leigh Rachal @ FPC Abbeville, LA

Last week, we heard the story of Elijah,

the prophet who called down fire on Mount Carmel

and listened for God’s voice in the sound of sheer silence.

Through Elijah, we saw God’s power and presence

breaking through a time of idolatry and fear.

After Elijah, the prophetic mantle passed to Elisha,

whose ministry was marked not by fire and thunder,

but by compassion: healing the sick, feeding the hungry,

showing that God’s Spirit moves among the people in everyday life.

Now, generations later, we meet another prophet: Amos.

The people of Israel have grown prosperous and comfortable.

Their worship is full of songs and sacrifices,

but their society has grown unjust.

Amos is sent to remind them that true faith

is not measured in offerings or rituals,

but in righteousness that rolls down like a river

and justice that flows like an endless stream.

Let us listen for the Word of the Lord in the words of the prophet Amos.

(Amos 1:1-2; 5:14-15, 21-24)

Generations later, Jesus stands in the temple during a festival

and uses that same image Amos used: water,

to speak of God’s Spirit that flows through those who believe,

Let us listen now for the Word of the Lord from the Gospel according to John.

(John 7:37–38)

Sermon: Come to the Water

There’s a certain kind of tired that doesn’t go away with a nap.

The kind of tired that comes from watching the world and whispering,

“Surely this isn’t what God had in mind.”

Maybe that’s how Amos felt.

He wasn’t a prophet by trade.

He didn’t have a pulpit, a robe,

or a professional headshot on the synagogue website.

He was a shepherd (a man who smelled like sheep) and,

as he liked to remind people, a “dresser of sycamore trees.”

Which sounds fancy, doesn’t it?

Like a profession you’d find on a sign in a charming little village:

“Amos & Sons: Fine Dresser of Sycamore Trees Since 750 B.C.”

But it wasn’t glamorous work.

Sycamore figs were poor folks’ fruit,

and to “dress” them meant going tree by tree, fig by fig,

and poking each one with a knife so it could ripen properly.Amos spent his days coaxing sweetness out of something rough.

And maybe that’s why God called him –

because he knew how to take something unripe

and make it ready.

Amos knew how to do slow, patient work.

He knew how to keep going when nothing changed overnight.

So God sends this fig-pricking, sheep-smelling man north to Israel,

a country that believed itself to be doing just fine, thank you very much.